When efficiency meets exciting: the story behind a new dedicated hybrid engine powertrain

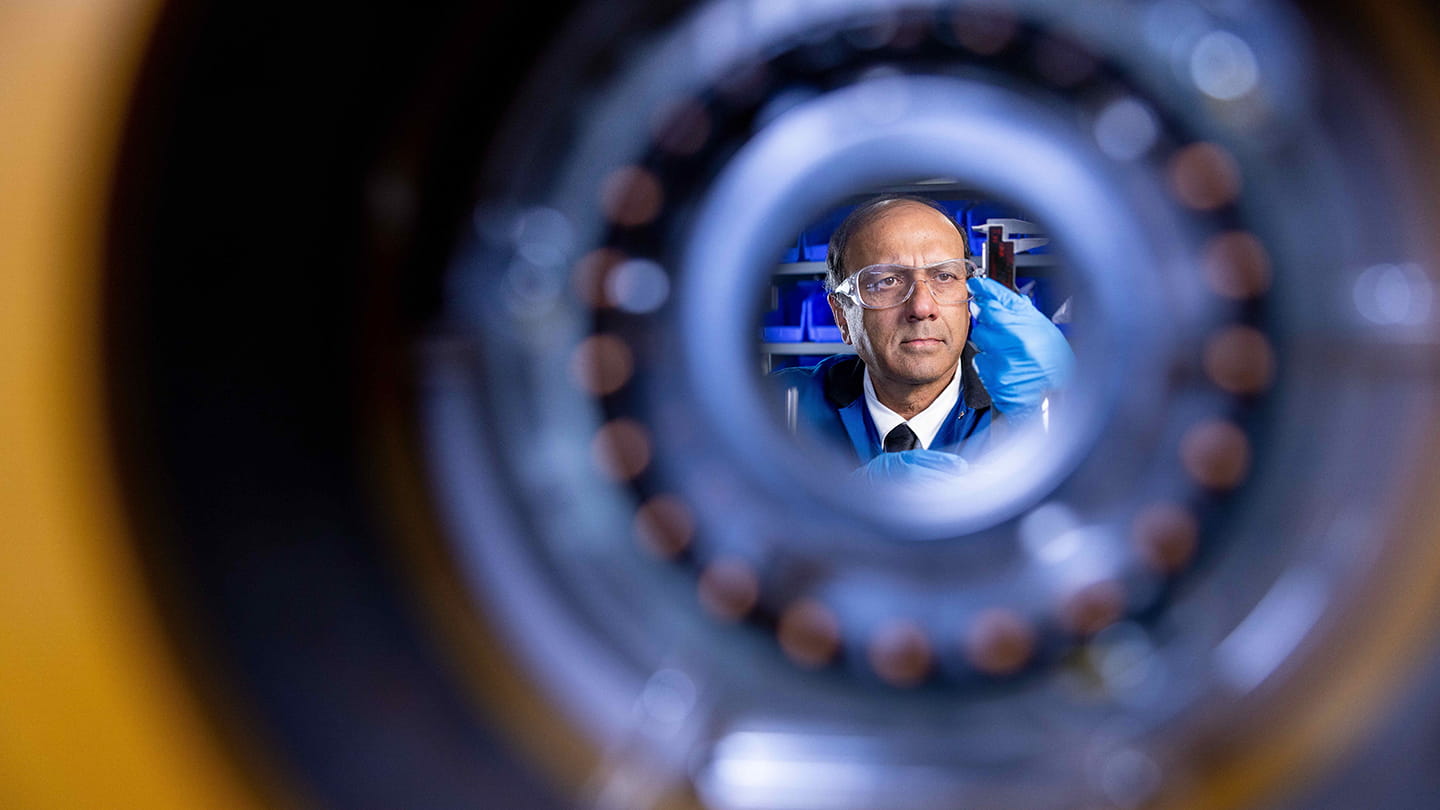

Nayan Engineer at the Aramco Americas Detroit Research Center, where the dedicated hybrid engine concept came to life.

A new dedicated hybrid engine from Aramco Americas began with a simple question: what would an engine look like if it were designed for hybrid operation from day one?

- Developed by Aramco Americas, in collaboration with Pipo Moteurs, this hybrid engine was conceived from the outset for hybrid operation, rather than adapted from a conventional design

- Its architecture prioritizes simplified manufacturing and lower cost, without compromising performance or drivability

- Early modeling suggests the approach could deliver a 23–25% cost reduction compared with today’s industry-standard hybrid systems

Aramco Americas Detroit Research Center experts are developing advanced solutions for the future of mobility.

“They saw it, they loved it, they said: ‘make it’.”

Nayan Engineer, Senior Combustion Specialist in Engines & Fuels Research at Aramco Americas’ Detroit Research Center, still remembers the moment he was given the green light to pursue an unconventional idea: a Dedicated Hybrid Engine (DHE) designed from the ground up to be a hybrid engine, rather than a conventional internal combustion engine retrofitted with electrification.

His ambition was straightforward but bold: create a powertrain that was more fuel-efficient, more cost-effective, and simpler to manufacture than existing hybrids; one that could maximize every mile from fuel, waste less as heat, and deliver smooth electric torque the moment the driver touched the accelerator.

The result? A refined hybrid engine that makes efficiency feel exciting.

Redefining hybrid powertrain architecture

The idea took shape during the Covid years. While the world slowed down, traditional Internal Combustion Engines (ICE) usage was disrupted, and headlines focused on newer full battery electric vehicles, conversations inside the Detroit Research Center told a more nuanced story.

“Hybrids really are the best of both worlds,” Nayan explains. “They give you the freedom of internal combustion — range, refueling ease, flexibility — while delivering the drivability and responsiveness people love in EVs. There are people who love EVs, and for good reasons, but tucked away in their garage is often a trusty old conventional engine car. Hybrids can span this difference.”

During this period, Nayan began envisioning a new hybrid architecture: one that combined lessons from existing systems but eliminated unnecessary complexity. Early modeling suggested significant manufacturing advantages, including fewer parts, simplified assembly, and a potential cost reduction of 23–25% compared with today’s mainstream hybrid designs.

After developing the concept using advanced CAD tools at the Detroit Research Center, Nayan patented the architecture and pitched it internally.

“Aramco really gives engineers the freedom to innovate — it’s in the company’s DNA,” he says. “I had the opportunity to present the idea to leadership. They saw it, they loved it, and they said: ‘Make it.’ That’s how it all began.”

Nayan Engineer, Senior Combustion Specialist in Engines & Fuels Research at Aramco Americas’ Detroit Research Center, still remembers the moment he was given the green light to pursue an unconventional idea: a Dedicated Hybrid Engine (DHE) designed from the ground up to be a hybrid engine, rather than a conventional internal combustion engine retrofitted with electrification.

His ambition was straightforward but bold: create a powertrain that was more fuel-efficient, more cost-effective, and simpler to manufacture than existing hybrids; one that could maximize every mile from fuel, waste less as heat, and deliver smooth electric torque the moment the driver touched the accelerator.

The result? A refined hybrid engine that makes efficiency feel exciting.

Redefining hybrid powertrain architecture

The idea took shape during the Covid years. While the world slowed down, traditional Internal Combustion Engines (ICE) usage was disrupted, and headlines focused on newer full battery electric vehicles, conversations inside the Detroit Research Center told a more nuanced story.

“Hybrids really are the best of both worlds,” Nayan explains. “They give you the freedom of internal combustion — range, refueling ease, flexibility — while delivering the drivability and responsiveness people love in EVs. There are people who love EVs, and for good reasons, but tucked away in their garage is often a trusty old conventional engine car. Hybrids can span this difference.”

During this period, Nayan began envisioning a new hybrid architecture: one that combined lessons from existing systems but eliminated unnecessary complexity. Early modeling suggested significant manufacturing advantages, including fewer parts, simplified assembly, and a potential cost reduction of 23–25% compared with today’s mainstream hybrid designs.

After developing the concept using advanced CAD tools at the Detroit Research Center, Nayan patented the architecture and pitched it internally.

“Aramco really gives engineers the freedom to innovate — it’s in the company’s DNA,” he says. “I had the opportunity to present the idea to leadership. They saw it, they loved it, and they said: ‘Make it.’ That’s how it all began.”

Developed by Aramco Americas, in collaboration with Pipo Moteurs, this hybrid engine was conceived from the outset for hybrid operation, rather than adapted from a conventional design.

How hybrids usually work—and what makes this one different

Most hybrid vehicles combine a gasoline engine with an electric motor and battery to reduce fuel consumption, improve efficiency, and lower emissions — particularly in urban driving — while retaining the practicality and range of a gasoline engine. The electric motor enables low-speed operation, recovers energy during braking, and assists during acceleration. In many cases, this hybrid system is added to an existing engine design; an effective approach, but one that can increase weight and complexity.

The DHE takes a fundamentally different path.

Instead of adapting a conventional engine, it was designed as a hybrid from the start. The engine and electric systems are integrated into a single, elegant architecture that performs efficiently across real-world driving conditions.

Electric motors are positioned at both ends of the crankshaft, simplifying the overall layout and allowing finer control of how power is delivered — creating opportunities for functions such as torque management typically associated with advanced electric vehicles. At the same time, the combustion engine itself is designed specifically for hybrid operation, rather than as a standalone engine adapted later.

The result is a compact, adaptable hybrid system that is efficient, scalable, and well suited to a wide range of vehicles.

Designs and decisions

With Aramco’s leadership backing secured, Nayan looked for a partner capable of translating his concept into hardware. He turned to Pipo Moteurs, a French engine manufacturer specializing in motor racing and known for housing design, analysis, manufacturing, and testing under one roof.

“Simply put, they’re engine people,” he says.

After presenting the concept, Nayan waited anxiously. When the response came, it was decisive: “You’ve got something special here.” What followed was a close, agile global collaboration built on shared vision and trust.

The core team was intentionally small: Pipo’s General Manager, Frederic Barozier, its Technical Manager, Anthony Buriez, and Nayan himself. Back in Detroit, only Nayan’s manager, David Cleary, was involved. This lean structure allowed the project to move quickly, without layers of bureaucracy.

The effort also had the support of Aramco’s Technology & Innovation leaders. “One of our executives came by my office on a visit to Detroit, saw the early mock-up and prototype, and simply said, ‘Make it,’” Nayan recalls. “That level of belief changes everything. Without that support, this project wouldn’t have seen the light of day.”

Pipo ran the engine for the first time on their test bench before shipping it to Detroit for further validation. The concept had moved from screen to steel — and it worked.

Most hybrid vehicles combine a gasoline engine with an electric motor and battery to reduce fuel consumption, improve efficiency, and lower emissions — particularly in urban driving — while retaining the practicality and range of a gasoline engine. The electric motor enables low-speed operation, recovers energy during braking, and assists during acceleration. In many cases, this hybrid system is added to an existing engine design; an effective approach, but one that can increase weight and complexity.

The DHE takes a fundamentally different path.

Instead of adapting a conventional engine, it was designed as a hybrid from the start. The engine and electric systems are integrated into a single, elegant architecture that performs efficiently across real-world driving conditions.

Electric motors are positioned at both ends of the crankshaft, simplifying the overall layout and allowing finer control of how power is delivered — creating opportunities for functions such as torque management typically associated with advanced electric vehicles. At the same time, the combustion engine itself is designed specifically for hybrid operation, rather than as a standalone engine adapted later.

The result is a compact, adaptable hybrid system that is efficient, scalable, and well suited to a wide range of vehicles.

Designs and decisions

With Aramco’s leadership backing secured, Nayan looked for a partner capable of translating his concept into hardware. He turned to Pipo Moteurs, a French engine manufacturer specializing in motor racing and known for housing design, analysis, manufacturing, and testing under one roof.

“Simply put, they’re engine people,” he says.

After presenting the concept, Nayan waited anxiously. When the response came, it was decisive: “You’ve got something special here.” What followed was a close, agile global collaboration built on shared vision and trust.

The core team was intentionally small: Pipo’s General Manager, Frederic Barozier, its Technical Manager, Anthony Buriez, and Nayan himself. Back in Detroit, only Nayan’s manager, David Cleary, was involved. This lean structure allowed the project to move quickly, without layers of bureaucracy.

The effort also had the support of Aramco’s Technology & Innovation leaders. “One of our executives came by my office on a visit to Detroit, saw the early mock-up and prototype, and simply said, ‘Make it,’” Nayan recalls. “That level of belief changes everything. Without that support, this project wouldn’t have seen the light of day.”

Pipo ran the engine for the first time on their test bench before shipping it to Detroit for further validation. The concept had moved from screen to steel — and it worked.

Nayan Engineer at the Aramco Americas Detroit Research Center, where the dedicated hybrid engine concept came to life.

Inside the engineering: old ideas, reimagined

With the concept and system-level architecture set, the focus shifted to execution — where the real tradeoffs began and engineering decisions had to balance efficiency, cost, and manufacturability. Because the engine operates within a narrow, hybrid-specific range — unlike conventional engines that must perform over a wider range— the team made an early decision to use a two-valve configuration rather than the four-valve layouts common in modern passenger vehicles.

“In most engines you have two intake and two exhaust valves, which means two camshafts,” Nayan explains. “By using one intake and one exhaust valve, we only need a single camshaft. That immediately reduces cost, complexity, and size.”

That choice set the direction for the rest of the valvetrain. The team adopted a pushrod architecture, a well-established system known for its durability, compactness, and low cost.

“It’s a proven mechanism,” Nayan says. “It works very well, and it allows us to keep the engine compact.”

This compactness mattered because one of the most effective ways to improve efficiency is a long piston stroke, which boosts thermal efficiency but can make an engine physically tall. The team addressed that tension through careful architectural choices. “In a sense, we traded height for length,” Nayan says. “We still get the efficiency we’re after, without introducing new constraints.”

None of these decisions were about novelty for its own sake. Each was rooted in established engineering practice, applied in a way that suited the engine’s role as part of a hybrid system. “There’s nothing here that would make a good engineer uncomfortable,” Nayan adds. “These are known technologies, used deliberately. Even today, some of the best motorcycle engines in the world still rely on pushrods.”

What comes next?

With the core concept proven, the focus now is on extracting maximum efficiency and refining electric motor integration, along with the associated control systems.

“That’s the next hurdle,” Nayan says. “But in principle, we know it works. As a concept, it’s on the table for anyone to pick up. We will showcase it at autoshows, engage with partners and car manufacturers, and they can run with it. We just want to see the idea go into production. To see something we’ve done benefit consumers and benefit the automotive industry.”

The current configuration targets a mid-size SUV platform, but the architecture is inherently flexible and can be scaled for smaller vehicles, particularly important for European and Asian markets. In terms of impact, Nayan sees particular value in developing and emerging markets, where affordability, fuel efficiency, and infrastructure realities make full EV adoption challenging.

“This engine is ideally suited for regions where mobility is growing fast, but cost matters,” he says. “It offers a practical balance between emissions reduction and real-world usability.”

A hybrid future, by design

Looking five years ahead, Nayan expects the DHE to evolve into a family of engines, adaptable across vehicle sizes and potentially suited for range-extended electric vehicles, where the engine functions primarily as a generator. But for him, the real point isn’t predicting the future. It’s responding to the present.

“Hybrids solve real problems today,” he says. “They work in cold weather. They work where charging infrastructure is limited. They work for people who care about efficiency but can’t afford uncertainty.”

For Nayan, the project also reflects what Aramco Americas brings to engine R&D, as part of Aramco’s technology innovation ecosystem: a culture that values execution over orthodoxy. “There’s a ‘do it’ mindset here in Detroit,” he says. “If the engineering is sound, you’re encouraged to test it. That freedom is rare — and it’s powerful.”

Ultimately, what he’s most proud of isn’t a single performance metric. It’s the decision to start from a clean sheet. “We didn’t try to fix an old engine,” he says. “We asked what a hybrid engine should be, if you were willing to rethink the assumptions. Aramco trusted me to ask that question… and to build a solution.”

With the concept and system-level architecture set, the focus shifted to execution — where the real tradeoffs began and engineering decisions had to balance efficiency, cost, and manufacturability. Because the engine operates within a narrow, hybrid-specific range — unlike conventional engines that must perform over a wider range— the team made an early decision to use a two-valve configuration rather than the four-valve layouts common in modern passenger vehicles.

“In most engines you have two intake and two exhaust valves, which means two camshafts,” Nayan explains. “By using one intake and one exhaust valve, we only need a single camshaft. That immediately reduces cost, complexity, and size.”

That choice set the direction for the rest of the valvetrain. The team adopted a pushrod architecture, a well-established system known for its durability, compactness, and low cost.

“It’s a proven mechanism,” Nayan says. “It works very well, and it allows us to keep the engine compact.”

This compactness mattered because one of the most effective ways to improve efficiency is a long piston stroke, which boosts thermal efficiency but can make an engine physically tall. The team addressed that tension through careful architectural choices. “In a sense, we traded height for length,” Nayan says. “We still get the efficiency we’re after, without introducing new constraints.”

None of these decisions were about novelty for its own sake. Each was rooted in established engineering practice, applied in a way that suited the engine’s role as part of a hybrid system. “There’s nothing here that would make a good engineer uncomfortable,” Nayan adds. “These are known technologies, used deliberately. Even today, some of the best motorcycle engines in the world still rely on pushrods.”

What comes next?

With the core concept proven, the focus now is on extracting maximum efficiency and refining electric motor integration, along with the associated control systems.

“That’s the next hurdle,” Nayan says. “But in principle, we know it works. As a concept, it’s on the table for anyone to pick up. We will showcase it at autoshows, engage with partners and car manufacturers, and they can run with it. We just want to see the idea go into production. To see something we’ve done benefit consumers and benefit the automotive industry.”

The current configuration targets a mid-size SUV platform, but the architecture is inherently flexible and can be scaled for smaller vehicles, particularly important for European and Asian markets. In terms of impact, Nayan sees particular value in developing and emerging markets, where affordability, fuel efficiency, and infrastructure realities make full EV adoption challenging.

“This engine is ideally suited for regions where mobility is growing fast, but cost matters,” he says. “It offers a practical balance between emissions reduction and real-world usability.”

A hybrid future, by design

Looking five years ahead, Nayan expects the DHE to evolve into a family of engines, adaptable across vehicle sizes and potentially suited for range-extended electric vehicles, where the engine functions primarily as a generator. But for him, the real point isn’t predicting the future. It’s responding to the present.

“Hybrids solve real problems today,” he says. “They work in cold weather. They work where charging infrastructure is limited. They work for people who care about efficiency but can’t afford uncertainty.”

For Nayan, the project also reflects what Aramco Americas brings to engine R&D, as part of Aramco’s technology innovation ecosystem: a culture that values execution over orthodoxy. “There’s a ‘do it’ mindset here in Detroit,” he says. “If the engineering is sound, you’re encouraged to test it. That freedom is rare — and it’s powerful.”

Ultimately, what he’s most proud of isn’t a single performance metric. It’s the decision to start from a clean sheet. “We didn’t try to fix an old engine,” he says. “We asked what a hybrid engine should be, if you were willing to rethink the assumptions. Aramco trusted me to ask that question… and to build a solution.”